How CCS technology can make the ‘storing 20’s’ a reality

By Ben Cannell, Innovation Director, Aquaterra Energy

The UK government recently announced Track 2 status for additional carbon capture usage and storage (CCUS) projects which will support carbon capture targets. The Acorn and Viking projects were selected as the third and fourth CCUS clusters in the UK – adding to HyNet and the East Coast cluster. This follows the ambition showcased in the Spring Budget 2023, where £20 billion in funding was announced for the early deployment of CCUS projects. These commitments highlight the UK’s commitment to serious CCS objectives, as the country aims to capture 10Mt of carbon dioxide a year by 2030. That figure equates to removing 4 million cars’ worth of annual emissions, so pulling this off will be no small feat. And given it’s already mid-2023, that leaves 6.5 years to reach that target from a standing start.

Will this be possible? And will the government support announced so far be enough to mark this decade as the Storing ’20s?

Who will pay the piper? And why?

The question of whether CCS is necessary is a settled one. However, the questions of who pays and how much are less clear cut. Most experts agree that the short-term economic case will come from coupling with hard-to-abate sectors like cement and emerging sectors like blue hydrogen. CCS technology like direct air capture advances means location might matter less, but for now, having projects geographically close to one another will be crucial. This geographic concentration can then lead to a situation where businesses pay a CCS operator to store their CO2 rather than releasing it into the atmosphere, but there are a lot of steps remaining before that can happen. It will cost to capture the CO2 and it will cost to transport it, and set up the related infrastructure, all before even getting offshore.

So, to the question of ‘how much’ – the answer is potentially quite a bit and relying on goodwill isn’t realistic. One viable option is setting a carbon price via tax or emissions trading, one that is high enough to incentivise companies to opt for CCS rather than releasing carbon into the atmosphere.

Carbon dating

Even if we establish a price that motivates behavioural change, there’s another challenge to tackle: who takes responsibility for stored CO2 and ensures it stays put?

In the short term, this is firmly in the hands of the CCS operator, but carbon storage will involve timelines spanning thousands of years, when even the longest-lived operators are unlikely to be around. For perspective, the world’s oldest operating company Kongō Gumi, dates back to 578 AD – roughly 1,500 years, a mere insignificance on a geological timescale.

Ultimately, there is no practical way to hold the private sector accountable over that timeframe and eventually responsibility can be expected to return to the state. Therefore, a stakeholder relationship needs to be established where the government clearly sets out the operator’s responsibilities and timeframe plus provisions for ongoing risk mitigation when responsibility is passed on.

In sight, out of mind

No one wants waste in their back garden, onshore CCS technology is unrealistic as a concept for that reason. One solution is storing CCS beneath the North Sea far from the ire of local communities. However, that doesn’t mean offshore CCS is free of public perception challenges.

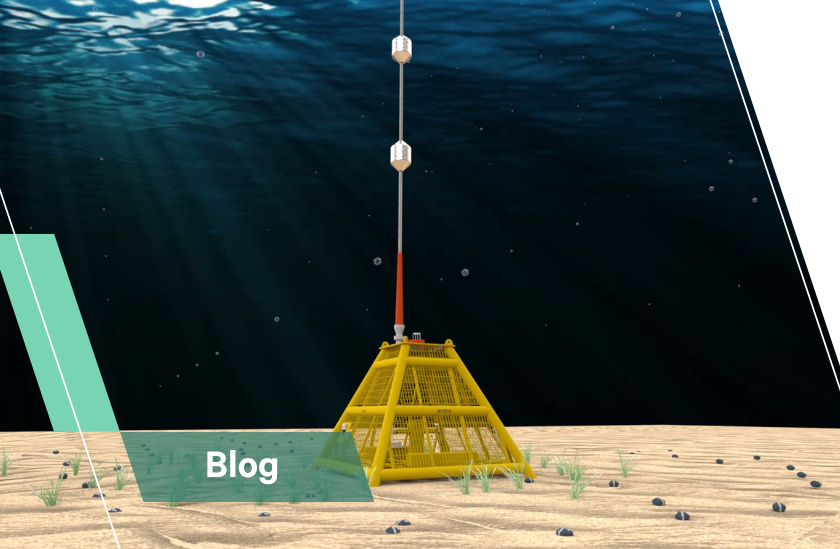

Engineering will play a crucial role to address these challenges. Monitoring is vital to ensuring that strict standards are followed, and CO2 avoids falling into unintended areas. Aquaterra Energy’s CO2 Monitoring Platform utilises field-proven technology to instil long-term confidence in the performance of storage sites. Even though some monitoring measures may seem redundant, their inclusion is essential to reassure the public and regulators. Like a fire alarm, they’re a safety net for unexpected issues, even if the engineering has been well-executed. Specifically tested CCS ready riser systems can further assist when dealing with concerns around CCS specific challenges, like sweet corrosion and extremely low temperatures.

From challenges to reality

Ultimately, it’s not engineering which is the main obstacle. The knowledge and CCS technology exists to handle these engineering issues at the pace required. At Aquaterra Energy, we’re already collaborating with operators on various studies for CCS from vertical re-entry of legacy wells and their potential re-abandonment, as well as subsurface and water column monitoring.

With the UK government demonstrating both the ambition and willingness to take action to ensure these projects become a reality, it’s now our job as engineers to execute and make the “Storing ’20s” a reality.

Learn more about our CCS offering here.